In this winter’s retreat, the month of January has passed and a new month begins in the silence, the cold weather, the stillness of winter. Whether the retreat is organized for us to be meditating as a group or alone, being the listener, the witness to the way it is, is the important issue. We’re not trying to get or get rid of anything but to just be the neutral observer, the Buddho, the witness to the way things are. This is bhāvanā – the Pali word for meditation and for developing the Eightfold Path.

During these days, many of you will experience a lot of suppressed memories or emotions that might arise, such as fear, guilt or remorse. Repressed anger or resentment can come up during these silent retreats. You can be rather frightened by it because sometimes we see a retreat like this as getting tranquil, getting samādhi and living in a blissful state where all the fears and anger, resentments, the world and all its complexities are suppressed and we're just in a one-pointed state of happiness that we'd like to hold on to.

Many times we may have been on retreats where we got various strong senses of samādhi, of luminosity, of peace, and then we want that again. We'd like to always feel like that, to feel enlightened, to feel blissful, to be free from fear and desire. When we practise meditation to get something, remember that the previous blissful experience is now a memory. So when you remember past experiences of being peaceful – feeling bliss through the silence of a retreat – you're remembering something that happened in the past, and that creates a desire to get to that state again. This is where being the witness is the important position to take – not the one who's trying to get something that you don't have in the present, that you remembered having on previous retreats. Be a witness to that very desire, the desire to get something you're not feeling, or that you don't have at this present moment. Much of our life is like this.

The cultural conditioning, the social conditioning that we've all experienced, very much sets up a habit pattern of repression. Cultural conditioning is about what's right and wrong, what's polite, what's impolite, what is true, what is false. You acquire these values from your parents, from your social group, and then carry them through life making value judgments about yourself and the world around you because of the cultural conditioning that you acquired when you were quite innocent, before you had any time to reflect on it. You just absorbed like a sponge, absorbed everything that was thrown at you, given to you, or what you were told was right and wrong.

During these retreats, maybe we have a lot of fear that arises over nothing in particular, either in the monastery or the immediate environment. Or maybe a lot of anger or resentment may manifest when you're in silent meditation. And then you try to get rid of it, that's one reaction, to suppress it, or feel that you can't meditate. Then you feel you're not a good monk or a good nun because you're feeling like this, or because the mind can proliferate, fight, resent. And all of this can be witnessed. All of us have a lot in life to resent because the life we experience from an ideal position isn't like that. It's not about justice and fairness where everything's right and your parents, social group, religious education – whatever it might have been – was right or wrong.

This word ‘conditioning’ is neutral. It's not about right conditioning or wrong conditioning, but conditioning itself through reward and punishment. When you're good, you get rewarded for that, and when you're bad, you're punished. That's the conditioning process. That's social and cultural conditioning that we experience. But witnessing that conditioning is not judging it in any way, but recognizing that there are a lot of repressed feelings, emotions, and desires. Resistance and repression are other forms of clinging. Vibhava taṇhā, the desire to get rid of or resist something, is like this.

Luang Por Chah had many stories to tell about how he dealt with fear. In Thai society, they are very much conditioned to believe in ghosts and spirits that you can't see but that exist in various places. That's very strong cultural conditioning. Being a dhutaṅga bhikkhu, a wandering monk, he would go and live in charnel grounds or graveyards where the suggestions and conditions for fear of ghosts or spirits would be most prominent. A graveyard always gives the impression of someplace you don't generally want to go into, even to someone who was not conditioned like that. It reminds you of death, and death is another fear we all have; fear of dying. In the worldly life, the sensory realm that we experience, there's a lot to fear. It's not an unreasonable emotion; it's primal to the animal world. The animal world is a world of survival and fear. Fear is a kind of protective mechanism, to be aware of where danger lies and try to avoid it. But because of memory, we can remember things even in the safest places and be frightened in our condo in London with locks on the door, guards at the gate.

Resentment is another example of conditioning. We have all maybe experienced unfairness in our lives, from teachers or parents who didn't understand what we were doing. Friends, or society in general, can make value judgments about us. Fear of what other people think is another strong social conditioning experience. ‘What will the neighbours think?’ But the ‘witness’ isn't thinking. It's not about thinking or deliberately trying to do something, but working with the way things are. You don't have to go to a graveyard to deal with fear of ghosts or spirits, or fear of something out there in the atmosphere that is some kind of menacing presence. We can consider just the way we can make ourselves frightened with what we're thinking or by remembering things of the past.

Fear is also an emotion that we sometimes like to experience. You wonder why people go to horror movies to be scared out of their wits by what they see on a screen. Why would you pay money to be scared? It’s because it is an exciting feeling, to be frightened and scared, to feel like you're a victim of life, a victim of society or a social group. There's something very egotistical about playing the role of a victim because it makes us feel that we're somebody who's been unfairly treated or victimized by something else outside ourselves. But the witness is aware. When one feels victimized by life, it’s like this. You're taking the position of ‘Buddhaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi’ – refuge in Buddha, to witness the way it is. It's not about getting rid of fear, or justifying everything and just trying to explain or analyze everything away. Or you try to think about it and analyze yourself, and blame your frightened tendencies on others. Or maybe you blame yourself, thinking you're just a weak person because you have a lot of fear to deal with. Whatever you think, whatever direction the critical mind takes, it's still words and thoughts and habits that you're using. You're not being a witness, you're being a critic – thinking about yourself, thinking about the world.

Sometimes one can relate to meditation, taking the witness position, as a kind of mental enema, a cleansing process. The word enema means a kind of cleansing process for the body, but this is a mental enema where we don't have to do anything but witness the mental conditions that arise. What comes out of your mind might be repulsive like any physical enema, but it's being released from yourself. You're letting go of it and allowing it to manifest, becoming fully conscious and not clinging to it. The Buddho is a refuge that we all refer to – Buddha as a refuge. It’s not refuge in some idealized Buddha of the past, not in some kind of traditional ceremonial chant, but it's about witnessing the way things are. When we talk about Gotama the Buddha’s enlightenment, he was witnessing the way things are, not trying to get rid of things, to fight or resist, or just get into a state where he didn't feel anything. There is that image of him under the Bodhi tree where he gives up trying to control his mind, trying to arrange everything, trying to get into a nice peaceful state. He just lets go of everything and then, as the legend goes, all the forces of the universe come and tempt him both on the fear and desire levels. His response is witnessing, not trying to control it, get rid of it, or condemn it, but just noticing, witnessing the presence and the absence of phenomena that arise. So it's a fearless position.

In my own experience, that's how I've learned to really develop or cultivate bhāvanā or sammā diṭṭhi, right understanding. It's not to fight or resist but to observe. Luang Por Chah’s definition of Buddho, the Buddha's name, is ‘the one who is a witness’. Knowing is like this. During this retreat, when negativity arises – fear, jealousy, anxiety, worry, doubt – see it as a blessing. It's asking to be let go of. It arises in consciousness when the conditions in a retreat here are not frightening. Amaravati Monastery is a very safe place in terms of external conditions. The community is trained with the vinaya – the precepts – so we’re committed to non-violence, to celibacy, to right speech; that's our intention as a group. In terms of safety it's as safe as you can get, where you have the community you're actually living and associated with, that makes such a strong commitment to moral precepts. So even if fear, jealousy, anxiety, worry, or doubt arise, don't take it personally. Don't see it as some kind of thing you've got to get rid of, or that if you want to get enlightened you've got to get rid of doubt. Because that very position of ‘I've got to get rid of doubt, get rid of fear’ is the ego again. ‘I'm somebody who has something I shouldn't have. If I were wise and enlightened, I wouldn't have any doubts or fears.’ That's an ideal we might create around Buddhist monks or nuns, or the Buddha himself. There is social conditioning, for example, the sīlabbata parāmāsa or attachment to conventions, social conventions, religious conventions. The vinaya is a moral convention that we attach to, not to create a sense of personality with it. We can become very arrogant when we look down on others who don't seem to have the high standards of moral conduct that we see in ourselves, that we are clinging to. It's not about creating a sense of moral superiority or condemning others, but they’re guidelines for action and speech in community life, in daily life.

Social conventions are something that we might not even notice. So much of Western psychology is based on the ego. We emphasize the word ego a lot, a sense of self-conceit or self-importance. It includes even an ego where we despise ourselves or look down on or criticize ourselves. Whatever habitual identity you form – an attachment to your physical body, or your physical identity – the ego comes from that strong conditioning, through social conditioning, through thinking.

Vicikicchā, generally translated into English as doubt, is the third fetter which prevents us from seeing the right path to sammā diṭṭhi. So we investigate doubt – to not be sure, to be uncertain, to be unstable, to not know something is like this. And that's about thinking, isn't it? You realize the danger of attachment to thought, how you create a whole world of expectations and fears just through thinking. We live in a realm of doubt and uncertainty and instability because the world is an illusion. It's not what you think. It's not a condition that you can control. The world arises and ceases according to other conditions. The sensory bodies we identify with are conditions: what we see, hear, smell, taste and touch – everything we think – is conditioned. Conditions can be skilful, kusala, or unskilful, akusala. But the Buddho, the knower, the witness, is aware. Skilful, unskilful, good, bad are all conditions created through thinking, through believing, through grasping. When you really penetrate that with wisdom, then the insight you get is letting go. It doesn't mean getting rid of the conditions, it means just releasing your grasp. In terms of samādhi or concentration, it's more like a relaxed state of awareness, not an intense grasping state of intense concentration on an object. It’s a sense of relaxation, of letting go, of releasing the body from all its tensions, releasing your mind from all its fears and desires. So when this happens, when we really trust in letting go, then sammā diṭṭhi – right understanding, or perfect understanding – arises. It’s there naturally. As individual people, we're not trying to be wise and get right understanding. When we think we're very wise and have sammā diṭṭhi, that's another conceit. After 55 years of monastic life, if I still think I have sammā diṭṭhi as a person, that's a delusion. Sumedho is an illusion, it's a costume, it's a convention. It's not a real person. But Buddho you can trust – conscious awareness in the present is like this.

Striving to get right understanding is good. There's nothing bad about it, wanting to become enlightened, wanting to become free from suffering, wanting to attain Buddhahood, wanting to become a bodhisattva. Wanting to become anything, like just a good person or a good monk or nun, that's good karma. It's good but it's still a convention. It's still a condition, a sense of me and mine – me, trying to become a very good monk or a good person, or get a good rebirth in the next life or even to get out of rebirth. Wanting to not be reborn again is still a thought, words that we read in the scriptures. These are good but the grasping of that, the sense of me and mine, ‘I'm somebody who doesn't want to be reborn again’, is like this. It's still a condition that arises and ceases. So, good is impermanent; bad is impermanent. The Buddho makes no judgments about good and bad anymore, it’s just knowing whatever condition you’re experiencing or attached to at present. The insight is to let go, to relax with it. Let it be what it is and it ceases all by itself. Allowing the natural cessation of phenomena is a relaxed open awareness, not an intense effort to destroy evil or get rid of the satanic forces in your mind or the universe.

To want to get rid of ignorance is a noble desire but it's still a creation of words. ‘I want to be free from all ignorance’ is a wholesome thought, but a thought is still a condition. Out of the habit of not understanding the way things are, or avijjā, we cling to these high-minded ideals, these goals, these conventions. The Four Noble Truths, the first sermon of the Buddha, is a really skilful tool to use to investigate that. We're not here to just become good people, good monks, good nuns, good samaṇas, good lay people. Even though that might be wholesome, or that what you think yourself to be as a person is making good karma, that very sense of being a person, a separate form in the universe, is a basic delusion of the ego, sakkāya diṭṭhi. You can't get rid of sakkāya diṭṭhi but you can know it by being the witness to it, whether it be a positive ego or a negative one is not the issue anymore. Perfectly healthy, well-adjusted, a normal personality or a neurotic one, these are judgments made in society. I've heard many people say, ‘I can't meditate, I don't have good karma. I've got to deal with all my repressed anger and fears and I need psychotherapy. I need to get rid of all of these obsessive ideas that come to my mind. I want to become a healthy personality.’ These are all good desires but it's still coming from the sense of total belief that you are what you think, what you're feeling, or what your emotions are. And as long as that belief goes unquestioned, then you're always going to experience suffering, no matter what you do, no matter how good you are.

We all have to witness the changing conditions of life, the COVID pandemic, climate change, the rumours, the political problems of various countries, seeing our parents grow old, get sick and die. We get attached to dogs and cats and then they die, and no matter how good you've been you still feel grief and sorrow at the passing of beloved pets. Is that good or bad or right or wrong? It's not about good or bad, right or wrong anymore, but it's when you attach, when this attachment is caused through ignorance, then we create suffering throughout our lives. Death is always the obvious end of a life. If your sense of self-worth is attached to what you look like, your body, or your social conditioning, beliefs, thoughts and memories, then you die in fear or with the hope to get a rebirth, there's still the desire to become. Some people fear death because they haven't been perfect in life. When people die, many times the relatives fear that they've made bad karma because they didn't tell this person that they love them enough, they didn't give them perfect care and love and total appreciation in their lives. You didn't visit them as often as you should have, so there's a lot of guilt when relatives or good friends pass away because we create this sense of what we should have done in the past. But no matter how good and caring we might be, death is the inevitable end of a birth. We've experienced birth already. We don't remember being physically born because we didn't have a language, we hadn’t developed memory with language to remember what it was like to be born. But we were conscious.

We acquire the cultural, even the religious attitudes about death, that’s social conditioning. Death itself is a rather frightening word for many people. It’s not considered polite to talk about death at social events. Even I find, when somebody dies, to say they're dead seems rather blunt. So we use the words ‘passing away’ or something less startling than ‘they're dead’. That seems so heartless, so final. But it is true, what is born dies.

So a mental enema is a cleansing. It's cleansing consciousness, allowing what you’ve repressed and feared to come into consciousness rather than just try to slam the door every time fear, doubt, anxiety, and worry arise. We get caught in that and spend our lives worrying about anything that we can worry about because it's become one of our thinking habits. The future always has the possibility to worry about something. The future is one big worry right now, isn't it? Who knows what's going to happen with pandemics, climate change, or universal problems like the universe we see and experience through the senses? We know we're all going to get old. And getting old means the physical form weakens; the senses fade and it's like this. But in awareness, the Buddho, the witness doesn't get old, isn't afraid, doesn't worry about anything, is not guilt-ridden, forgetful or blaming or feeling victimized. These are all mental constructions that we tend to hold in us. When they enter the door of consciousness we develop habits of resistance, of repression.

In bhāvanā, or meditation, the fearlessness of the attitude of Buddho, of witnessing the way it is, is not a witness that is afraid. It's aware of fear. So, what is Buddho; what is the witness position? We can call it conscious awareness, mindfulness, pure consciousness or whatever. The word doesn't matter as long as you understand what it really means, that just to be aware of this present moment is like this. Now that sounds very simple in words, but the conditioning process is complicated. Sometimes we have to deal with just witnessing loneliness, boredom, and conditions that we don't want. We don't want to feel alone or lonely or left out. We don't want to feel bored with life. These are created through the idea that life should be just one interesting experience after another. But no matter how many interesting experiences you've had in your life, life is quite boring really. That's why people go to horror shows, because they're bored. Then they feel excited, frightened, horrified, and that's a state they can feel alive with. But boredom, what do you do with it? How do you cope with boredom? How can you get rid of it? Of course, the usual way is to distract yourself with something interesting. Saṁsāra vaṭṭa, the worldly life that we identify with, is an endless seeking of distractions, because otherwise just being consciously aware like this seems like boredom to the thinking mind.

With the thinking mind, you can excite yourself with thoughts. It’s interesting to analyze yourself, or considering your astrological sign you become more interesting as a person because you're born under a certain sign, and the stars and the sun and the moon were all in alignment, and this creates a sense of self-interest. So astrology can be very interesting. Or self-analysis: Why do I fear? Why do I suffer? Who's to blame for it? That can be very interesting because we didn't all come from happy home lives where our parents were absolutely perfect, or from a life that has been perfectly fair. So who's to blame for my suffering? Who can I blame?

Praise and blame are worldly dhammas, or worldly conditions. Praise is what we're after, what we want. That's exciting and interesting. To be praised, to be acknowledged, to be respected, to be admired is very pleasant. To be disregarded, ignored or condemned is very unpleasant. Modern life is very much aimed at trying to become something – become a famous person, become a rock star, become president of the United States, become somebody that's in the news, win a beauty contest, join the French Foreign Legion or some exciting militia group. They're very exciting, to be fighting for righteousness – to be a fighter for human rights, a fighter for democracy, a fighter for freedom. That gives you a sense of being somebody who’s on the right side of goodness and skilfulness. We can devote ourselves to good causes, to peace movements, to social justice, to democratic principles, to the rule of law, to all the best that we can think of. One considers that's good karma. It might be, but it might also not be very good karma because so many righteous groups are very deluded. If feeling righteousness is what you're aiming for, to make everything right according to what you think or according to what you've been told, this can be a form of tyranny. If I am attached to righteousness and you don't agree with me, then you're wrong. And what does that mean in terms of relationship? Then that's a kind of absolutizing of right and wrong. You become absolutely wrong and I become absolutely right. How can there be any communication between right and wrong except through destroying what's wrong; go on righteous wars to kill off the evil forces or the wrong views of others? So we get caught in endless wars. We get news of terrorism, killing, murdering, collateral damage; bombing people, villages and so forth where a lot of innocent people get killed out of a sense of righteousness, of clinging blindly to being right, or for principles such as standing up for democracy. That's exciting, that's not boring. But when you talk to men and women who have been in military lives and dealt with conflicts and wars, wars are quite boring actually. So much of it is waiting around. But when we go to the cinema and watch war movies it's all very exciting. Excitement is available to us, it's a distraction. But boredom is what we don't want, so we ignore it and seek various ways to find pleasure, happiness, comfort, romance, adventure, and excitement. And that's the world. The world is like that and that's why it's an illusory world. It's not the real world that everyone claims it is. It's the world of different illusions that individuals hold and grasp out of ignorance.

So in this retreat, I encourage you to not to take sides with any issues but to investigate. This investigation, how is it done? It's not an investigation of who is right and who is wrong but it's a witnessing, observing, like a really mindful soldier who's out in the field observing, just open to life, and the sounds and sights that are in the present moment are like this. But the soldier is interested in trying to identify any dangerous enemies lurking in the forest or on the horizon. We're not looking for enemies but just observing, witnessing Dhamma, ultimate reality, supreme reality – whatever words you want to use for it, it's apparent here and now, so it's available every moment. That's where we experience life. It's always here and now – it's like this. Just sitting here in the Temple is like this. Breathing is like this. Sitting is like this. What is it that’s aware of sitting? Are you aware of sitting or is sitting just the natural movement of the body: sitting, standing, walking, lying down? Do you force yourself to breathe? You can take pranayama lessons and develop all kinds of exercises with the breath. We're not asking you to do that. We're encouraging you just to be the awareness of the inhalation; it's like this, and the exhalation is like that. It sounds very boring, but getting through boredom is where wisdom lies. When life becomes boring – when you get old, life is increasingly boring. During a winter retreat, where there's nothing to do but sit, stand, walk, lay down, watch your breath, it’s very boring. Then we think of all kinds of things we should do to get rid of the boredom. But boredom is a mental state. It's not ultimate reality. What is ultimate reality? What is supreme reality, here and now, is conscious awareness. And that's where boredom ceases, where loneliness ceases, where the ego collapses, disappears; where the social conditioning, conventional attachments, disappear. You're not resisting or denying them, but they naturally cease. They’re mental states that arise and cease. They're very ephemeral and have no substance.

So it's up to you as individuals. What I've said this afternoon is an encouragement because one thing I can do is encourage you. The Buddha’s teachings are very skilful directions on how to end suffering. The First Noble Truth is about suffering, to be understood. The Third Noble Truth is the end of suffering. The ‘end of suffering’, what does that mean, that you don't get old, you don't get sick anymore, you don't feel grief when your beloved mother passes away or when your favourite cat dies? It means you're aware of grief, of old age, and you're not attaching to it. It doesn't make you cold-hearted and indifferent to life, but it allows empathy to arise in social situations. You don't become a totally unemotional zombie. Then you feel the wisdom of the brahma vihāras. That’s what's left when you’ve let go of everything – mettā, karuṇā, muditā and upekkhā. That’s how we relate to the deluded world, the illusory world that we're experiencing through the forms that we no longer identify with. So I offer this as a reflection.

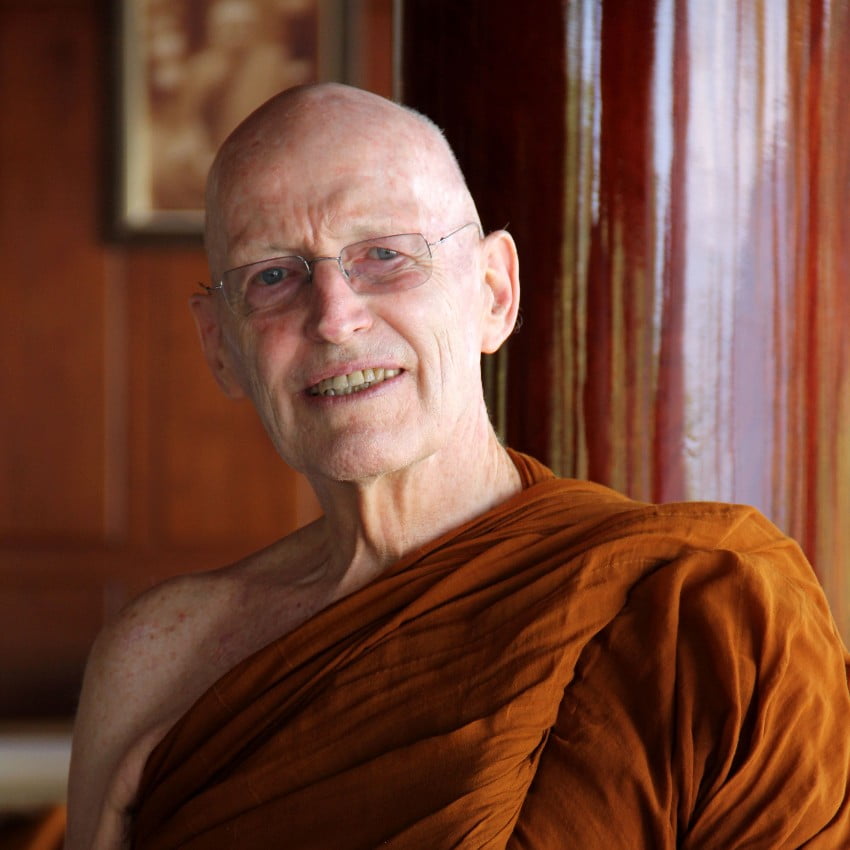

More articles by Ajahn Sumedho

The Way It Is

Ajahn Sumedho

This is the half-moon Observance Day, and we have the opportunity to reflect on Dhamma, the way it is. For each one of us, the way it is right now is going to be different: with our own moods, memories,... อ่านเพิ่มเติม

Reflections on mettā

Ajahn Sumedho, Ajahn Sucitto, Ajahn Amaro, Ajahn Jayasaro

The Practice of Mettā by Luang Por Sumedho There is a great lack of mettā in the world today because we have overdeveloped our critical faculties: we constantly analyze and criticize. We dwell on what is wrong with ourselves,... อ่านเพิ่มเติม

Dhamma Reflections – Doom, Destruction, Death, Decay

Ajahn Sumedho

Doom, Destruction, Death, Decay This journey is involved with pain, with loss, as well as with pleasure and with gain. This realm isn’t a realm that we create out of our fantasy life; this realm is the way it... อ่านเพิ่มเติม

Remembering Tan Ajahn Buddhadāsa

Ajahn Sumedho

I’ve always regarded Ajahn Buddhadāsa, along with Luang Por Chah, as one of my primary teachers. I could relate to their way of teaching because it was so direct and simple. Ajahn Chah wasn’t intellectual at all – he hardly... อ่านเพิ่มเติม

Thoughts on Practice in a Thai Megalopolis

Ajahn Sumedho

Well, I think you’re doing it at this center. It is a special place. Thai people are open, they want to know. I’ve seen significant change in the many years I’ve been connected to Thailand, especially in the middle class.... อ่านเพิ่มเติม