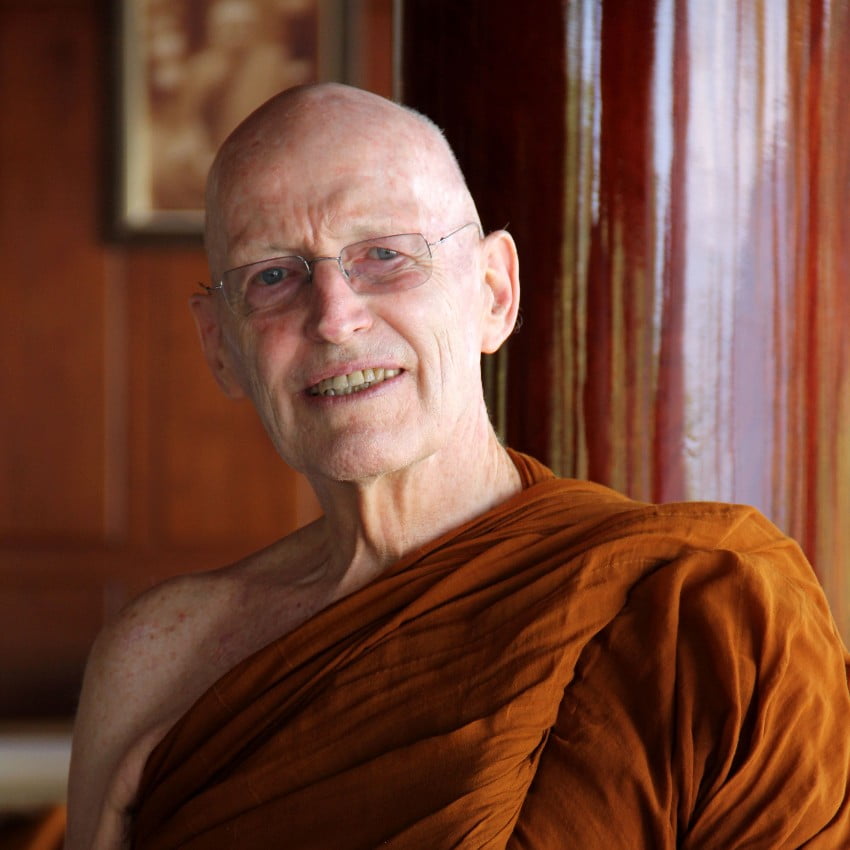

The Practice of Mettā by Luang Por Sumedho

There is a great lack of mettā in the world today because we have overdeveloped our critical faculties: we constantly analyze and criticize. We dwell on what is wrong with ourselves, with others, with the society we live in. Mettā, however, means not dwelling in aversion, but being kind and patient even to what is bad, evil, foul or terrible. It’s easy to be kind to nice animals like little kittens and puppies. It’s easy to be kind to people we like, such as sweet little children, especially when they are not ours. It’s easy to be kind to old ladies and men when we don’t have to live with them. It is easy to be kind to those who agree with us politically and philosophically and who do not threaten us in any way. It is much more difficult to be kind to those we don’t like, who threaten us or disgust us. That takes much more endurance.

First we have to start with ourselves, so in traditional Buddhist style we always start the practice of mettā by having mettā for ourselves. This does not mean we say: ‘I really love myself, I really like me.’ When we practise mettā towards ourselves, we no longer dwell in aversion to ourselves. We extend kindness to ourselves, to our conditions of body and mind. We extend kindness and patience even to faults and failings, to bad thoughts, moods, anger, greed, fears, doubts, jealousies, delusions – all that we may not like about ourselves.

From Ajahn Sumedho Anthology Vol 1 – Peace is a Simple Step

Mettā to Others as to Myself by Ajahn Sucitto

The mental kamma that we walk around inside tints our world. So it’s important to keep acknowledging this, and also to provide supportive perceptions, so you don’t just keep sitting in the old kammic bath water wondering why it doesn’t get any cleaner. So, the practice of kindness, beginning at home — my general advice is to first of all receive it. Allow yourself to receive it. Just bring up that impression: what does it feel like being given something? One of those silly cards that say you’re the greatest in the world; bunch of flowers; glad to see you — that kind of impression — what’s that moment like? What’s the feeling when it’s coming this way — instead of something else that you’ve got to do to support others or so forth — what’s it like coming this way?

So you can bring up a very simple idea and even an image or recollection like that — what’s it like to be given to? Then when you’ve lengthened and steadied your attention span and are just able to dwell in that impression, how does it feel in your body? Do you feel any sense of being a little more relaxed or brightened up? Less contracted? Something in the nervous system seems to tone up. You feel appreciated, valued, loved, respected, given. Typically, touching acts of kindness come not because you’ve done something but just from free will. So it’s not a matter of ‘deserving it’. It’s not an auction, you know, how much are you worth today? Just the sense of free will, not what you’ve done, but what you are — how that feels. You can sense something happens in your whole system — it just tones up. This is where the mettā bhāvanā begins.

Reflection and guided meditation by Ajahn Sucitto, from a retreat in November 2007.

On Love by Ajahn Jayasaro

To live wisely in this world involves learning and understanding the nature of love and contemplating its disadvantages as well as its advantages. The Dhamma teaches us to abandon cravings which are the cause of the suffering and the harm that accompany mundane love. We should aim to be one who neither suffers from love nor causes suffering for others on its account. We should purify our love so that it takes on more and more the qualities of mettā. Learning from experience leads us to the truth of things. When we see the way things are, the love that is fuelled by ignorance and craving will diminish or disappear altogether. The love based on wisdom, understanding, and the desires that spring from them will persist and mature.

In Dhamma practice, wisdom acts as the direct antidote to ignorance by examining the reality of life and the world with a stable, stilled and unbiased mind sustained in the present. The direct antidote to craving is the systematic and integrated development of wholesome mental states. In the case of love, the most prominent of these virtues are loving-kindness and the effort to be a good friend. Training ourselves to practice restraint, to keep track of our emotions, to let go: these are at the heart of the negating side of the practice. But at the same time we need a positive ideal to cultivate. That positive ideal is provided by the pure love called mettā. The distinguishing characteristics of a pure love are:

- It is unconditional.

- It is boundless, a wish for all living beings to be well.

- It is not a cause of suffering.

- It is governed by wisdom and equanimity (upekkhā).

It is a miracle that such a love exists, and that every single human being has the ability to develop it. When we watch the news and see the cruelty and heedlessness of our fellow human beings, the feelings of depression and despair that can arise may be dispelled by reflecting on our innate ability to feel mettā. It’s true that human beings can be awful creatures, but it’s also true that they have it within them to be better than they are.

From On Love

How does mettā practice benefit the world? by Ajahn Amaro

When we use the English word love, we tend to blur it into meaning liking. And when you are developing loving-kindness meditation towards yourself, then you’re not trying to pretend that you like your tendencies towards selfishness, anger or jealousy, or you’re not pretending that you like your laziness, your greed… Or, in relationship to other people, that the people who’ve hurt you in your life or caused you great harm or who you see causing harm to others, you’re not saying you’re approving or you like what they do, or that the things that they have done are pleasing, but you can recognize that this happens in nature, that there is violence in the natural world, that some people act in ways that are harmful and destructive.

We ourselves might have some habits, tendencies, things that we’ve done that were really regrettable. We’re not trying to pretend that we like them, but what we’re recognizing is that this is the way things are. These qualities of selfishness, greed, anger and jealousy — they exist in the natural world, they’re part of the natural order. So when we practice loving-kindness towards ourselves and towards all other beings, then it makes more sense and it’s more meaningful to consider this in terms of a radical acceptance of all beings. You’re not trying to pretend you’re liking the unlikable, but you’re recognizing: ‘Here it is. This is the way things are.’

More articles by Ajahn Sumedho, Ajahn Sucitto, Ajahn Amaro or Ajahn Jayasaro

Mental Enema

Ajahn Sumedho

In this winter’s retreat, the month of January has passed and a new month begins in the silence, the cold weather, the stillness of winter. Whether the retreat is organized for us to be meditating as a group or alone,... Citește mai mult

The Way It Is

Ajahn Sumedho

This is the half-moon Observance Day, and we have the opportunity to reflect on Dhamma, the way it is. For each one of us, the way it is right now is going to be different: with our own moods, memories,... Citește mai mult

Dhamma Reflections – Doom, Destruction, Death, Decay

Ajahn Sumedho

Doom, Destruction, Death, Decay This journey is involved with pain, with loss, as well as with pleasure and with gain. This realm isn’t a realm that we create out of our fantasy life; this realm is the way it... Citește mai mult

Thoughts on Practice in a Thai Megalopolis

Ajahn Sumedho

Well, I think you’re doing it at this center. It is a special place. Thai people are open, they want to know. I’ve seen significant change in the many years I’ve been connected to Thailand, especially in the middle class.... Citește mai mult

Remembering Tan Ajahn Buddhadāsa

Ajahn Sumedho

I’ve always regarded Ajahn Buddhadāsa, along with Luang Por Chah, as one of my primary teachers. I could relate to their way of teaching because it was so direct and simple. Ajahn Chah wasn’t intellectual at all – he hardly... Citește mai mult