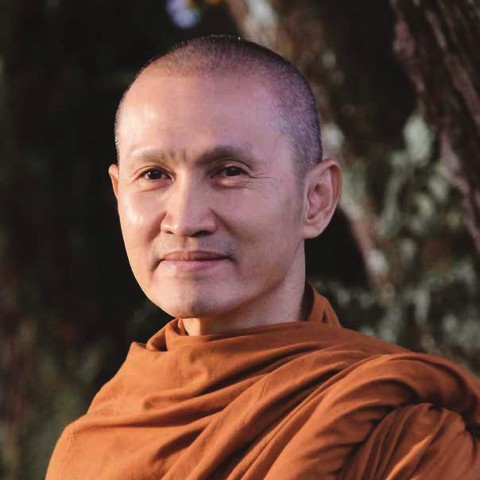

Ajahn Dtun

Venerable Ajahn Dtun (Thiracitto) was born in the province of Ayutthaya, Thailand, in 1955. At the age of six his family moved to Bangkok and he remained living there until June 1978. From a young age he was a boy whose heart naturally inclined towards having a foundation in moral discipline. By the time he was a teenager and on into his university years there would be many small incidents that would fashion his life and gradually steer him away from the ways of the world towards wishing to live the Holy Life.

After graduating in March 1978 with a Bachelors degree in Economics, he was accepted into a Masters Degree course in Town Planning at the University of Colorado, USA. However, in the period that he was preparing himself to travel abroad many small insights would amalgamate in force and change his way of thinking from wishing to take his studies as far as he could and then lead a family life, to thinking that after graduating he would remain single and work with the aim of financially assisting his father until the time was right for him to ordain as a monk. One evening he happened to pick up a Dhamma book belonging to his father which opened, by chance, at the last words of the Buddha: ‘Now take heed, monks, I caution you thus: Decline and disappearance is the nature of all conditions. Therefore strive on ceaselessly, discerning and alert!’ Reading over this a second and then a third time, the words resonated deeply within his heart causing him to feel that the time had now come to ordain, knowing this was the only thing that would bring any true benefit to him. He resolutely decided that within two months he would ordain as a monk and that his ordaining would be for life.

In June 1978, he travelled to the north eastern province of Ubon Ratchathani to ordain with the Venerable Ajahn Chah at Wat Nong Pah Pong. Resolute by nature and determined in his practice he was to meet with steady progress regardless of whether he was living with Ajahn Chah or away at any of Wat Nong Pah Pong’s branch monasteries. In 1981, he returned to central Thailand to spend the Rains Retreat at Wat Fah Krahm (near Bangkok) together with Venerable Ajahn Piak and Venerable Ajahn Anan. The three remained living and practicing together at Wat Fah Krahm until late 1984. At this time Venerable Ajahn Anan and Venerable Ajahn Dtun were invited to take up residence on a small piece of forest in the province of Rayong in Eastern Thailand. Seeing the land was unsuitable for long term residence, Ajahn Dtun chose another piece of land that was made available to them - a forested mountain that would later become the present day Wat Marp Jan.

After spending five years assisting Venerable Ajahn Anan in the establishing of Wat Marp Jan, he decided it was time to seek out a period of solitude so as to intensify his practice, knowing this to be necessary if he were to finally bring the practice of Dhamma to its completion. He was invited to practice on an eighty-acre piece of dense forest in the province of Chonburi and remained in comparative isolation for two years until 1992 when he eventually decided to accept the offering of land for the establishing of a monastery - Wat Boonyawad. Presently, the monastery spreads over 160 acres of land, all kindly given by the faith and generosity of Mr and Mrs. Boon and Seeam Jenjirawatana and family.

Since allowing monks to come and live with him in 1993, the Venerable Ajahn has developed a growing reputation as a prominent teacher within the Thai Forest Tradition, attracting between forty to fifty monks to come and live, and practice, under his guidance.