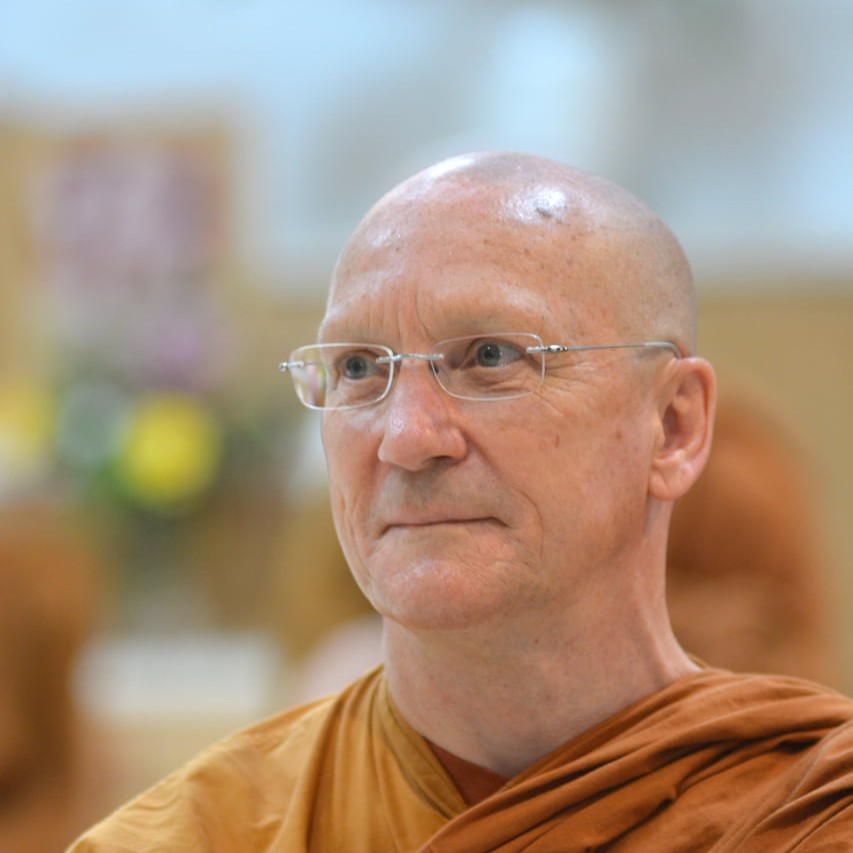

Ajahn Pasanno

Ajahn Pasanno took ordination in Thailand in 1974 with Venerable Phra Khru Ñāṇasirivatana as preceptor. During his first year as a monk he was taken by his teacher to meet Ajahn Chah, with whom he asked to be allowed to stay and train. One of the early residents of Wat Pah Nanachat, Ajahn Pasanno became its abbot in his ninth year. During his incumbency, Wat Pah Nanachat developed considerably, both in physical size and reputation.

Spending 24 years living in Thailand, Ajahn Pasanno became a well-known and highly respected monk and Dhamma teacher. He moved to California on New Year’s Eve of 1997 to share the abbotship of Abhayagiri with Ajahn Amaro.

In 2010 Ajahn Amaro accepted an invitation to serve as abbot of Amaravati Buddhist Monastery in England, leaving Ajahn Pasanno to serve as sole abbot of Abhayagiri for the next eight years. In spring of 2018, Ajahn Pasanno stepped back from the role of abbot, leaving the monastery for a year-long retreat abroad. After returning from his sabbatical, Ajahn Pasanno now serves as an anchor of wisdom and guidance for the community [at Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery, CA, USA]